Systems thinking for more effective disaster management

I attended an excellent IPAA Queensland session in September on ‘Rethinking Crises and Achieving Resilience in a post-COVID world’ with a panel comprised of Alistair Dawson (Inspector-General of Emergency Management), Professor Cheryl Desha (Queensland Disaster Management Research Alliance, Griffith University), Collin Sivalingum (State Emergency Services Manager, Red Cross) and Dr Anne Tiernan (Constellation Impact Advisory, Griffith University). The panel was exceptionally generous in sharing challenges and lessons from work in the sector (and from the past few years especially), which made for an excellent and honest discussion. Here I share my thoughts on how evaluation is relevant and useful to disaster management.

Disaster preparation, response, recovery, and resilience efforts are multi-layered and complex. To add further complexity, the frequency and severity of disaster in Australia is changing. Increasingly communities are dealing with the overlapping impacts of multiple disaster events, which means preparation and planning for future disasters is having to take place while communities are still enmeshed in recovery efforts.

The panel raised several challenges faced in recent disasters that provide important learnings to inform future service planning and delivery.

Disasters cross jurisdictions but information often doesn’t

Disasters happen across jurisdictional borders. This means there are a diversity of state and territory coordination and delivery frameworks at play. As stated in the recently released McKell Institute report,

“Australia’s national arrangements for coordinating and delivering disaster management are complicated and fragmented, with roles and responsibilities split and overlayed between various levels of government, as well as between numerous departments and organisations. There is no shortage of different frameworks at play, each with its own plans, bodies, committees, and stakeholders.”

It’s not uncommon for each participating jurisdiction or agency to have its own (different) operating system. At best, this makes data sharing difficult and slow: at worst, data sharing can be impossible: the panel provided an example of a worker transcribing material manually from one laptop to another during disaster response because the systems didn’t speak to each other.

There is often a temporal element to data sharing: it may be more feasible during the response phase of disasters (for example, when declarations of states of emergency support sharing) but no longer accessible in the recovery phase. This can limit efforts to support impacted communities to recover as quickly as possible.

Another issue of cross-jurisdictional information coordination is that public preparedness and safety campaigns and messaging differ across states. This can potentially impact the safety of citizens moving across borders. For example, Queenslanders are broadly familiar with the advice that ‘If it’s flooded, forget it’. However, interstate visitors who sheltered in Queensland evacuation centres during the recent floods had not heard this message. The panel saw an opportunity to collaborate across borders on campaigns, to ensure people are receiving the information they need, regardless of where they are domiciled.

Recommendations repeat across inquiries

While there have been numerous inquiries and Commissions specific to natural disasters, they are all largely similar in their scope. This tends to mean that the recommendations from each inquiry are very similar, rather than expanding on what’s known from past inquiries (the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC identified 140 post-event reviews and inquiries since 2009, and identified a significant number of parallel recommendations) . The panel termed this ‘institutional amnesia’.

Preparation and resilience require year-round collaboration and communication

Communities’ demographics have undergone large shifts during the past few years, with the migration of Australians between states during COVID-19 lockdowns, and emerging communities (such as newly arrived community members escaping conflict in Ukraine). The dynamic nature of communities poses challenges to ensuring the whole community understands and is considered in disaster responses. The panel discussed the need for a community development approach: one where disaster services are working year-round in communities, to maintain the lines of communication and sense of common purpose achieved during the response phase of a disaster over time.

Response frameworks aren’t always flexible enough to ‘see’ or reach everyone impacted by disasters

The panel identified the need to ensure that response and recovery is designed in such a way that it can reach everyone. For example, basing eligibility for disaster relief payments on postcodes won’t reach people experiencing homelessness, or populations who aren’t directly impacted but who experience vicarious trauma and still need support services. The panel suggested harnessing the co-productive power of the community itself to create more effective preparedness campaigns and recovery efforts.

Shifting to a systems lens

The panel discussed the shift in thinking that needs to occur in order for some of the mistakes and challenges of the past to be avoided in future. They summarised their one key message from discussions, which were:

- Courage –to expose ourselves to thoughts and conversations that haven’t been had before.

- Relationships – critical to build and maintain, and to keep having conversations over time.

- Community – keeping community at the centre of what we do.

- Sustained collaboration.

The overarching theme I took away was the need for a shift to systems thinking, and that the relationships between actors in the system need to be strengthened and maintained over time.

What does this mean for how we design and evaluate disaster preparedness, recovery and resilience efforts with communities?

In a recently published blog, Amy Gullickson and Wolfgang Beywl pose a question, that feels highly relevant to evaluation of disaster management efforts.

“With globalization and the awareness promoted by natural science research [in the 2000s], not only the values and interests of the respective stakeholders but also those of future generations came to the fore [in evaluation] … The key question for evaluation science now is what role should it take in view of urgency and unpredictability? (Beywl, W and Gullickson, A, 2022).

Discussing systems evaluation with my colleague Andrew Hawkins recently, he raised the point that there is oftentimes a mismatch between an acknowledgement that a problem needs a systems response, and that the planning of its evaluation is still conceived from a non-systems perspective. The desire for evaluations to provide findings on ‘how much change’ can be attributed to a strategy or program is in ideological conflict with a systems evaluation approach, which sees the system and relationships between parts of the system first.

Andrew said, ‘the old mechanistic worldview uses analysis to develop knowledge of what makes a good “bit” or response. The new systems world view uses synthesis to seek to understand how good is the “fit” between the bits. This doesn’t mean we don’t care about the performance of bits or interventions; it just means we are less focused on developing knowledge of stable cause and effect relationships about bits (or measuring outcomes that we think will repeat in other times and places) and more with understanding the deficits between the bits in any particular system and then intervening to fix those deficits. Not all problems should be addressed from a systems perspective – but once a problem has been defined as a system problem then interventions and evaluations of those interventions should determine what is needed “here and now” rather than seeing this as an opportunity to test “what works” in any time and space invariant manner.’

For me at least, this conversation and the panel’s focus on the strength of relationships between parts of the system, raised questions about how we might need to shift mindsets – not only of the disaster management sector, but also of the sector’s evaluation commissioners – about what constitutes useful knowledge in an evaluation.

Reflecting on the session recalled to mind a quote from ‘The Dawn of System Leadership’, I recently highlighted in a piece about Mental Models for ARTD’s newsletter (August 2022): ‘transforming systems is ultimately about transforming relationships among people who shape those systems’. This transformation requires ‘opening the mind (to challenge our assumptions), opening the heart (to be vulnerable and to truly hear one another), and opening the will (to let go of pre-set goals and agendas and see what is really needed and possible).’

I was also prompted to think again about considerations of timescale in program design and evaluation, given the need to forecast future interventions in order to have a hope of keeping ahead of disasters. This is best summed up by Andrew in an earlier blog:

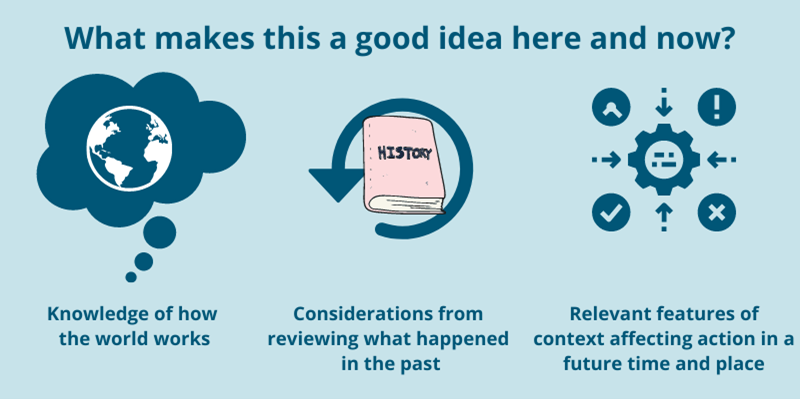

“It is highly likely that evaluating claims about the future value of action are more crucial to our survival as a species than claims about what happened in the past. If evaluation is to stay relevant in our complex social world, it must evolve from a focus on past endeavours in specific times and places, to providing ways and means of determining the value of a current or future action in a dynamic and uncertain future. One way of doing so is paying more explicit attention to the question of ‘What makes this a good idea, here and now?’. Truly evidence-based answers will incorporate our best knowledge of how the world works with considerations from reviewing what happened in the past, combined with understanding of the relevant features of context that will affect the success of a proposed course of action in a future time and place. The idea of prospective or propositional evaluation as a means for determining the value of a proposed course of action is still yet to be realised” – Andrew Hawkins (read the blog in full).