On Time – are evaluators concerned with the past, the present or the future?

Evaluators are more often than not brought in to determine the value of some action after the fact, or ex-post. Economic evaluators are sometimes brought in to determine the value of a proposed action as part of a business case, or ex-ante. Evaluators are also useful when undertaking monitoring to ensure an action is on track as it is being implemented, or ex-itinere (or from the journey). This raises the question, is evaluation concerned with the past, the future or the present?

Despite numerous articulations of different types of evaluation[1], the core concern of those commissioning evaluation is often determining the merit, worth, or significance of something, based on evidence about what happened in the past. All facts by their nature live in the past. Past effects of action are extremely valuable for informing, but not constituting answers to questions about whether or how we should do something now or in the future. But, answering this question of ‘what happened’ is rarely the deeper purpose of an evaluation, which is to inform decisions in the present moment relating to the value of a particular initiative in an uncertain future.[2] We should not confuse the retrospective methods that evaluation often employs with the prospective function that evaluation most usefully serves.

A very common injunction placed on evaluation, and task assigned to evaluators is to determine ‘what works?’ or ‘what works for whom in what contexts and to what effect?’. In providing answers to these questions, facts are necessarily derived from studies of ‘what happened’. But notice, the temporal orientation in the question in ‘what works’ is not ‘what happened’. The temporal orientation is the present perfect tense: the question ‘what works?’ assumes that an answer about what happened in the past will continue to apply in the future. This assumes we can find causal laws that are time and space invariant (or at least consistent if not invariant), or as the realists would put it, find causal mechanisms in context that are replicable and ‘transfactual’. If this was so, why then, after so much time and money has been spent on evaluation, do we have so few answers to the question of what works?

The attempts to establish causal relationships in the human world are as old as natural philosophy and science. The goal of finding laws (and by association programs or actions) that offer a ‘constant conjunction of cause and effect’ is still alive and well, however there is relatively little in the complex world of human affairs that can be said to have been found to ‘work’ across a great diversity of contexts.

The core assumptions that warrant us looking backwards in order to look forwards, work well when applied to physics and chemistry because of the degree of regularity that can be found in associations of cause and effect. Here a phenomenon in nature can be isolated and studied ‘in-itself’ and its predictable future effects understood. Natural systems as in biology can also be studied scientifically as they tend towards equilibrium and stability despite their dynamic nature and sensitivity to external ‘shocks’ as with the case of algal blooms in a river. This behaviour provides us with the idea of how large changes can occur in non-linear ways. Yet we know people in society are different, they are interdependent and highly adaptive to their context[3]. They also adapt much more rapidly as a result of their ability to consciously (and un-consciously) think and consider their behaviour and that of those around them in making new decisions.

The people running and participating in a program are not immutable but are in a state of constant movement and change; they have good days and bad days, some part of them is growing and developing while another is disintegrating and withering away. And none of us are independent of each other. The decisions of people with whom we come in contact cause us to change our own. The value of action in a homeless shelter is always dependent on and determined by the many people involved directly with a person in that shelter and their own level of wellbeing, as well as indirectly by people in other domains of interest for the program, in the homelessness ‘system’ more broadly, which includes family and friends as well as broader macroeconomic trends.

The difference in studying ‘what works’ in the natural science and the social world led many since ancient Greece to the dialectical method, or reasoning, as a guide to evaluation in a dynamic, uncertain, and contested world about ‘what is likely to work here and now’. In such a context, the scientific imperative to categorise and determine laws and regularities is less useful than to seek to understand a system and respond with a reasonable proposition. Amongst such social complexity, evidence-based policy is not primarily useful when concerned with the evidence used for establishing claims about what happened in some time and place, but evidence to support claims about the value of a proposed course of action, here and now.[4]

The ability to infer from the past as a guide to the future must be recognised for the difficult and inherently uncertain task that it is. When considering a current or past endeavour we may consider that a future context will share some similar characteristics to a past, as a past endeavour may bear resemblance to a future incarnation of it. However, in an increasingly interdependent and connected world of adaptive people and organisations, context will not only vary by location, but constantly differ from what went before: the person that attended an education program yesterday will not get the same value from the program tomorrow, and the impacts on them as a result of attendance may be different if they attended the program tomorrow instead of yesterday. In such complexity, how can we predict anything other than the most macroscopic of phenomena?

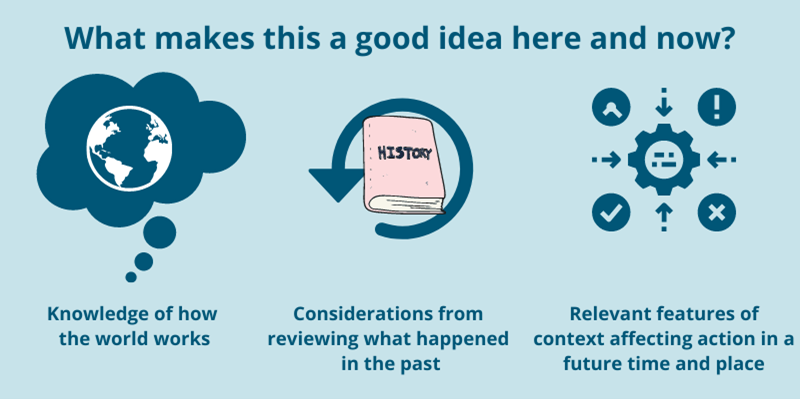

It is highly likely that evaluating claims about the future value of action are more crucial to our survival as a species than claims about what happened in the past. If evaluation is to stay relevant in our complex social world, it must evolve from a focus on past endeavours in specific times and places, to providing ways and means of determining the value of a current or future action in a dynamic and uncertain future. One way of doing so is paying more explicit attention to the question of ‘What makes this a good idea, here and now?’. Truly evidence-based answers[5] will incorporate our best knowledge of how the world works with considerations from reviewing what happened in the past, combined with understanding of the relevant features of context that will affect the success of a proposed course of action in a future time and place. The idea of prospective[6] or propositional evaluation as a means for determining the value of a proposed course of action is still yet to be realised.

There is a role for evaluation in considering questions about past, present and future action. In any given project we need to get clear on what we really need to know from an evaluation. We need to know whether we are doing a history project (what happened?), a scientific project (what are the causes of this class of phenomena?), or a pragmatic project to inform present decision making in an uncertain future world (should we do it?’).

Making change in the social world is more often about applying science than doing science. An understanding of scientific theories about human and social behaviour are necessary but not sufficient for designing an intervention that actually works. Just as an effective bridge leverages scientific theories about the world (torsion, gravity etc) a specific bridge will be evaluated as to whether it was a ‘good’ idea to build one here, based on whether it was built to known quality specifications, and whether people use it. So too in the social realm we are not testing theories about how the world works, we are attempting to leverage them. We never take the design of a successful bridge and simply keep building the exact same design, yet we tend towards this idea that programs can be understood and replicated because we have measured their past outcomes.

It would seem to me that the most important thing to think about in addressing social and environmental problems is evaluating present decisions about current or future action, not fixating on the value of past effects. Evaluating past effects is useful to provide accountability, but evaluation for learning is only useful when that learning can inform present or future[7]decisions about a current or proposed action. As evaluators we should be ready to provide our clients with tools for prospective evaluation of a proposed course of action using a dialectical method coupled with empirical data collection.

The confluence of science, history, context, and action will determine the value of any action and can be expressed in a logical claim about the value of a current or proposed course of action. It is my hope that evaluation will evolve from a concern with warranting specific policies or programs as ‘evidence-based’, towards a concern with enhancing the extent to which claims about current or future action are ‘evidence-based’. This occurs when we set out and evaluate propositions about specific actions in a certain time and place, before and during their implementation.

We need to move to an understanding that ‘what works’ is not any specific program, but a process of understanding of systems dynamics, the judicious use of logic, knowledge of past effects and real time data that can confirm or deny whether the conditions we thought necessary for success were actually brought about by our actions, and were indeed sufficient for our intended outcome. Only then will we find an answer to that much talked about, but not so often answered perfect present tense question, ‘what works’?

The position set out in this blog aligns with much evaluation that is actually practiced today and may represent an ‘implicit’ theory of evaluation for many practicing evaluators. In this sense it is nothing new for the many wise hands that practice evaluation. It does however stress that evaluation is about applying social science[8], and as such, needs a theory of evaluation that is closer to engineering than to physics, one that is focused on the value of current or future action rather than one focused on establishing stable cause and effect relationships.

Notes

[1] This blog is mainly concerned with impact evaluation rather than the many other important forms of formative, development or empowerment evaluation. This is because impact evaluation, whether in the experimental or realist tradition, is most sharply focused on making scientific claims about cause and effect across time and space.

[2] This does not run so far as to ask ‘what is to be done’ for this is clearly a political question – but the likely value of any particular answer to that question does lend itself toward evaluation.

[3] We recommend pairing this blog with On Context.

[4] See Hawkins 2020 Putting the Logic back into Program Logic.

[5] Evidence being a property of claims not programs, just as ‘validity’ is a property of judgments or inferences and not of methods per se. This is one reason that no single method can be considered ‘valid’ across time and space. It is not the method, but the claims drawn as a result of using the method that can be subject to claims of being valid or not. Similarly, programs per se cannot be evidence based while claims about their effects can be evidence based.

[6] https://www.gao.gov/products/pemd-10.1.10

[7] The problem of the duration of the present moment is not a pragmatic question, nor one we will dwell on here, but is one that philosophers have wrestled with since Zeno and Parmenides.

[8] Campbell, D. T. (1984a). Can we be scientific in applied social science? In R. F. Connor , D. G. Altman , & C. Jackson (Eds.), Evaluation studies review annual (Volume 9, pp. 26-48). Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications.