THE COST BENEFIT ANALYSIS APPROACH TO ECONOMIC EVALUATIONS: BENEFITS AND BARRIERS

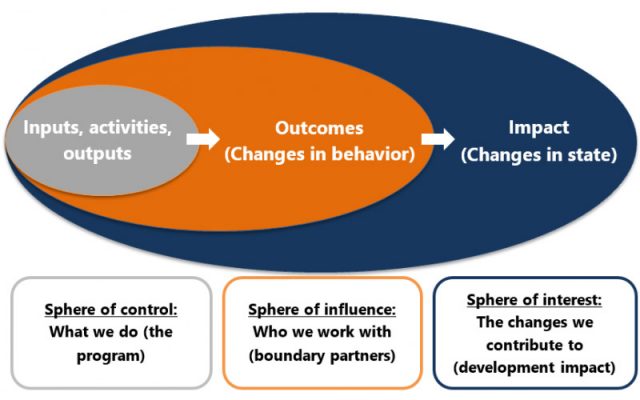

Building on ‘new public sector management’ reforms of the 1990s, the NSW Government’s shift to Outcomes Budgeting in 2017-18 meant a mindset shift away from measuring expenditure on outputs towards allocating funds to achieving outcomes for people, with more integrated outcomes targets and performance tracking across agencies. At the same time, they released updated guidelines for measuring costs and benefits, identifying Cost-Benefit Analysis as the preferred economic evaluation method to assess proposals.

Interested in applying the latest thinking from NSW Treasury, Moya, Ken and Natasha recently participated in an Australian Evaluation Society interactive online session on Economic Evaluation: Benefits and Barriers, presented by Ophelia Cowell from the Centre for Evidence and Evaluation at NSW Treasury, and Dr Julian King, a public policy Consultant and Director at Julian King & Associates.

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

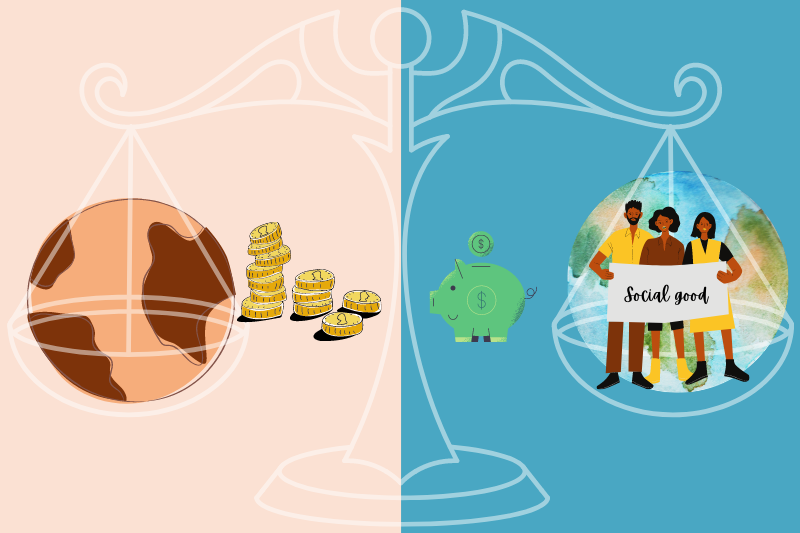

A Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) is a systematic approach to calculating and comparing the benefits and costs of a course of action in a given situation, against a ‘base case’ (generally business as usual/ no policy change). A CBA can be designed and implemented either during or following a program or policy.

As a tool for decision makers, CBA can provide a rationale for pursuing one option over another, by providing a valuation of each option’s economic, social and environmental costs and the benefits in monetary terms (both now and weighted into the future). The process of conducting a CBA can also help program designers and policy makers consider whether a particular program is a good idea or sensible investment.

CBA STRENGTHS

As Julian pointed out, CBA can be useful for allowing evaluators to provide an ‘approximate answer’ to the question: ‘Is society better off?’ This is because:

- both costs and benefits are measured in the same units ($) and can be adjusted and weighted over many years

- CBAs have similar guidelines around the world and generally follow a systematic replicable process (noting that analytical decisions around what data is included and its level of importance in calculations may vary from evaluation to evaluation)

- analysis can be undertaken to understand different scenarios and/or minimum numbers required for a policy to break even and be considered a success (for example, the minimum number of polluting vehicles traded in for cleaner transport alternatives)

- projections and estimates can be made around the likely future uptake of a particular program in other locations (for example, the take up of e-bikes or electric vehicles in a particular location)

- comparisons across programs and/or policy sectors can be made, although should be undertaken with caution.

CBA WEAKNESSES

While both presenters identified the value of CBA and noted how useful and important it can be, they also expressed caution about exclusively relying on a CBA.

For example, if a person trades in their petrol car for an electric vehicle, the costs associated with reduced fuel usage and emissions can be monetarily measured. But it can be harder to derive a meaningful monetary valuation of that person’s increased level of happiness associated with driving a cleaner vehicle, and/or the feeling they are making a positive/ cleaner contribution to the environment.

Some key challenges and weaknesses associated with CBA that were highlighted included that:

- qualitative data may not be collected, analysed and reported on

- cost and benefit projections do not always occur as intended and might lead to policy failures

- there is an emphasis on efficiency and utility, focusing on the end result rather than the process or how equitable it may be

- there is an assumption of what is wanted, prioritising the majority rule which can exclude the feedback and insights of minority stakeholders

- it produces simplified models of the world, meaning its predictions don’t always line up with the complex messiness of the real world (where unforeseen events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can greatly impact CBA costing and projections)

- data limitations around quality and availability may exist.

MIXED METHOD APPROACHES

Considering the strengths and weaknesses of CBA, Julian urged evaluators to mix disciplines and methods so that we make holistic evaluative judgements. He suggested that while CBA can form part of our evaluations, it is not an evaluation on its own and should be integrated in our wider evaluation practices.

Julian promoted the use of rubrics as one approach for integrating a mix of quantitative and qualitative data to make a transparent evaluative judgement.

APPLICATIONS

We are currently working with a health training organisation to conduct an evaluation of an online education program. Our work will include a value for money assessment using qualitative and quantitative data sources. To do this we will do a cost consequence analysis, to measure the intangible values of the program (such as course enjoyment), against the cost of implementing and running the program. We will use a similar framework proposed by NSW Treasury to ultimately determine the value of the training program.

We look forward to continuing the discussion around economic evaluations and participating in future interactive AES sessions.