Having the difficult conversations

R U OK? day and World Suicide Prevention Day this month serve as reminders to have the necessary – though challenging – conversations about the mental health concerns and suicidality with which many people wrestle every day of the calendar.

One very clear metaphor which communicates the conditions (very often structural) which create extreme psychological distress comes from the Ukranian author Maria Tumarkin. In Axiomatic (which also explores suicide and the ways it can impact communities) Tumarkin writes:

“One way of putting it is that many…live their lives on a highway where they are repeatedly hit by passing trucks. As they are bandaging their wounds, cleaning them out with rainwater, putting bones back into sockets, another truck’s oncoming. A backlog of injuries functions not unlike a backlog of grief, an expression I first heard near the desert in the Kimberleys where backlog describes the unrelenting holding of funerals on Aboriginal land, leaving the living no time to mourn the dead, creating an imploding paralysis…Most people have a truck going over them at some period in their life. But on a highway you don’t get one or two. You get a convoy. They don’t stop. That’s the point. The recurrence is the point. The point’s the repetition.” – Maria Tumarkin, Axiomatic, p. 89

The additional stressors of the past few years of the pandemic are evident in the high numbers of Australians experiencing psychological distress. The National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics found 15% of Australians experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress in 2020–21, with a greater incidence (20%) in the 16–34 year old age group.

Given the prevalence, it’s important that everyone understand what mental illness is, its drivers and what it can feel like. It’s also important for people to feel capable and confident to talk about mental health, so they know what to do and potentially how to help (without necessarily having to ask ‘how can I help’, which can place a greater mental burden on someone experiencing mental illness). Tools like Movember’s ‘Movember Conversations’ and training like Mental Health First Aid courses can help with mental health literacy and practicing difficult but vitally important conversations.

In our work, these capabilities are essential, as we’re increasingly evaluating initiatives designed to support those with mental illness and those experiencing suicidality. In our work we have involved lived experience researchers to identify appropriate ways to have conversations with people who have experienced suicidality so their voices can inform evaluation. Some of the things we do are:

- Working with lived and living experience (LLE) researchers to ensure our methods, approaches and timing are appropriate and trauma-informed – understanding ways to talk safely about suicide.

- Recognising the importance of the first point of contact with a person who has experienced suicidality as an opportunity to build trust and demonstrate understanding.

- Equipping people invited to participate with information to help them make an informed decision about participating, while recognising their expertise in their own safety planning.

- Having LLE researchers on the team to do interviews and interpret the findings so people feel more comfortable to participate.

- Being conscious of how we end interviews, helping people to ground back in the present if they have been reflecting on difficulties in the past

- Having LLE researchers supporting the analysis to ensure the findings are interpreted accurately in context.

In this work, we also have to be conscious of the mental health of our team so that they turn up able to have these conversations. This means planning for our own mental health, being able to step back from a project completely or for a time if it is impacting us, having opportunities to debrief and access to external supports if we need.

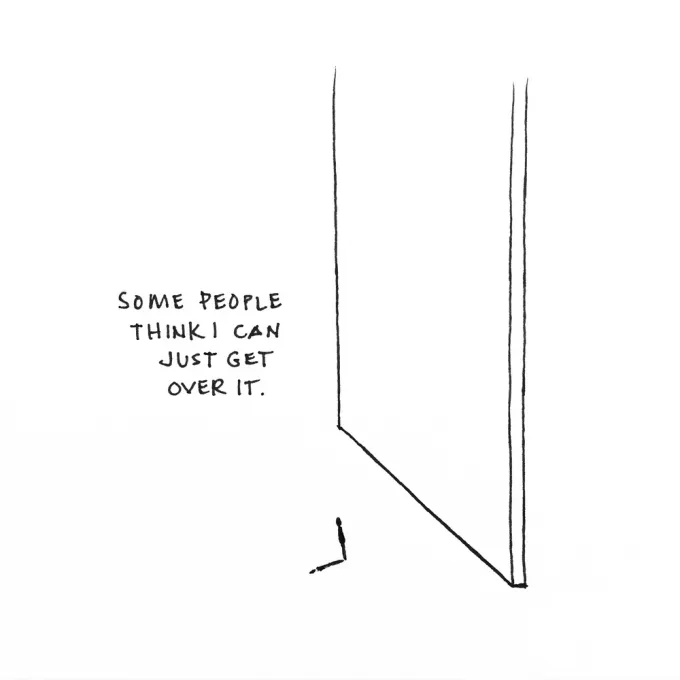

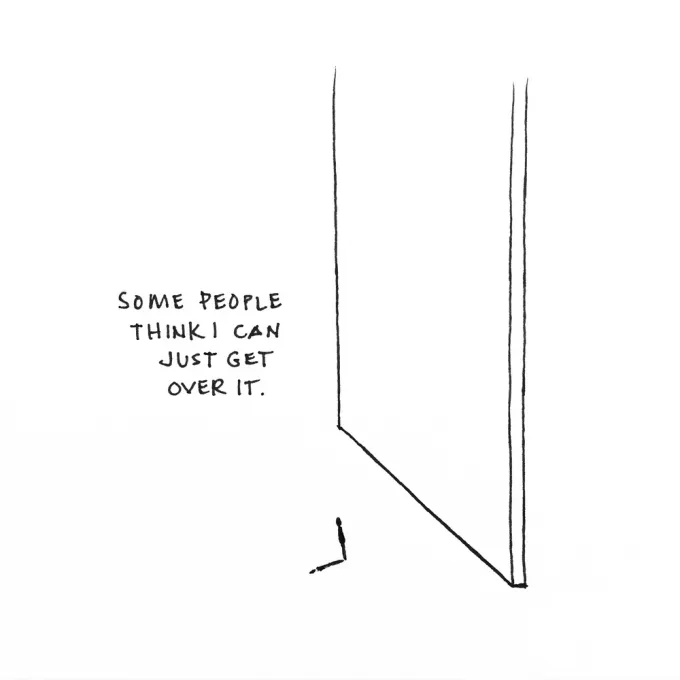

Image source: Project1in4 by Maria Bentley

We’re also conscious in our evaluations of the need to understand not only individual experience but the broader systems and how these affect implementation of supports and individual experience and outcomes. Tumarkin’s highway metaphor, and the rest of her complex and unflinching exploration of society and mental illness in Axiomatic, serve as a reminder that while having conversations with those around us who are struggling is important and can even be life-saving, this is but one piece of the broader work needed to shift the values, structures and systems in our societies that can drive or exacerbate mental illness and suicidality. That’s the other difficult conversation we need to continue to shape together, as a society.