Comparing apples and oranges using rubrics

Have you ever been asked to compare two different programs? Or have you been asked to look at a group of projects from a grant program to evaluate how the overall program is doing? Did you feel that it was like comparing apples and oranges?

You’re not alone – it happens all the time. Fortunately, there’s an easy to use, transparent tool that can help you do just that. I even got to talk about it at the recent AMSRS ACT Conference, Evidence, insights and beyond: Enhancing Government policies, programs and services, in Canberra last Tuesday.

The conference brought together public servants, researchers, evaluators and not-for-profit organisations to explore ways to collect and translate evidence into meaningful insights and apply them to enhance Government policies, programs and services.

Conference highlights

Before I get to telling you how you can compare apples and oranges, I thought I would give you some of my highlights from the conference, as it covered some broad ground. Keynote speakers, Lisa Bolton and Penny Dakin, both gave excellent presentations on research and survey design in the current policy environment, while Brian Lee-Archer gave us a glimpse of how evaluation is incorporating bigger and broader sources of data, and how to do this effectively.

The breakout session on behavioural insights brought us up to speed on the latest work to incorporate behavioural insights in policy development, from improved communications with doctors to reduce the over-prescription of antibiotics to using general population surveys as a way to characterise and test ‘nudge’ interventions outside of the laboratory.

I was lucky enough to be a speaker in the session on evaluation capability, where I followed two great talks on the subject. First, Duncan Rintoul walked us through the process of developing a robust evaluation culture. Then Josephine Norman related her experience of establishing an internal evaluation unit in a government department, and how to make it successful.

Comparing apples and oranges using rubrics

So how do we compare apples and oranges when it comes to having multiple programs or projects under a single policy umbrella?

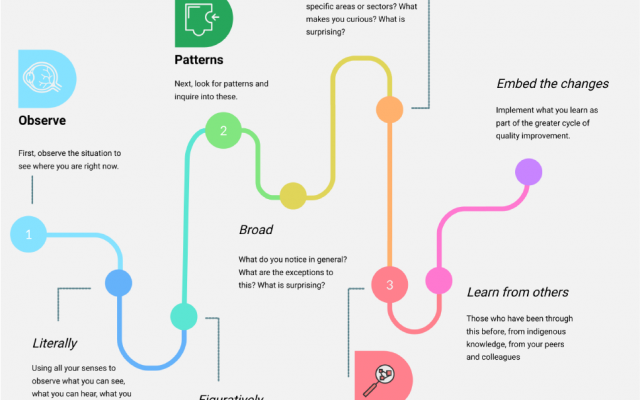

The answer is to use rubrics as a tool for creating a common framework for comparison. Rubrics, for those of you who haven’t encountered them before, are a way of defining what constitutes ‘good’ for a program or policy, setting out explicitly what the qualities of performance are and the different levels of performance (e.g. poor, average, good, very good). If it sounds a little bit like a grading sheet from your schooldays, then you’re not wrong.

Rubrics came from the education domain but have been increasingly used in evaluation as they are transparent, able to use qualitative and quantitative evidence together, and can be developed in culturally responsive ways to incorporate different value systems and ways of knowing. Evaluators like E. Jane Davidson, Nan Wehipeihana, Judy Oakden and Kate McKegg have been pioneers in developing the rubric approach for evaluation.

The frontier for rubrics is in applying them not just for a single program, but to a portfolio of programs; here they are a powerful tool. Using policy goals as a guide, you can develop a rubric that acts as a common framework for evaluating a range of programs that are designed to address common policy objectives. This way you can compare programs against each other, and collectively assess programs to understand the portfolio performance.

Rubrics aren’t the complete solution and, used alone, they can have drawbacks – they don’t capture program-specific goals, external factors and unintended outcomes. That is why using program-specific program logics and outcomes matrices is important. They enable you to capture other program goals and to clearly define the evidence you need to capture to measure outcomes. What is key is that your rubrics, program logics and outcomes matrices are designed to work together with a common language and connection.

A real-world example of portfolio evaluation using rubrics

This is all somewhat abstract, so in my presentation I showed an example of how we used a rubric at ARTD through our work with the NSW Office of Emergency Management to evaluate the National Disaster Resilience Program (NDRP) in NSW between 2013 and 2015. The evaluation covered six separate funding programs delivered by four agencies, under a policy framework incorporating three separate policies. The activities delivered by these programs ranged from building fire trails to volunteer recruitment and training through to cutting edge scientific research. In other words, not just apples and oranges, but an entire fruit salad.

By developing a rubric approach in partnership with an expert advisory committee of program managers, delivery partners and academia, we were able to create a tool that articulated what constituted good performance for the NDRP. Using this tool, we gathered and analysed evidence that enabled an understanding of not just how the individual programs and their activities contributed to meeting policy objectives, but also how the portfolio of programs worked together to build community resilience to natural disasters.

Bringing it together

It was a great opportunity to be able to attend the AMSRS ACT Conference, and an even greater opportunity to pass on our insights from comparing apples and oranges in policy evaluation, because we know it’s a common challenge in government agencies. Most importantly though, the strong attendance at the conference showed a clear interest from the public service in evidence-based policy making and in building evaluation capacity in the workforce. This is a positive sign for policy development, delivery and evaluation.

If you’re keen to learn more about how to use rubrics in evaluation, Davidson’s book, Evaluation Methodology Basics, is a great place to start, with a concise and practical overview of how to design and apply them to programs.