Reducing domestic and family violence: the power of stats and stories

One in three Australian women older than 15 years have experienced physical violence. Almost one in five have experienced sexual violence. Each week, a woman is murdered by a current or former partner.[1] And while domestic and family violence (DFV) is increasingly on the national agenda, preventing violence against women is a relatively new and growing field of policy development.

In Australia today, there are a myriad of policies and programs aimed at preventing and responding to DFV. At the national level, efforts are guided by the The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010‐2022 and its Fourth Action Plan. In NSW, system reform is set out in the NSW Domestic and Family Violence Blueprint for Reform 2016–2021: Safer Lives for Women, Men and Children, led by Women NSW.

The DFV sector is also guided by Change the Story, the world’s first framework for a consistent and integrated national approach to preventing violence against women and their children. Change the Story reflects an important shift that is occurring in the sector—it brings a gendered lens to understanding violence, making it clear that gender inequality lies both at the heart of the problem and solution to violence. It also recognises that reducing DFV requires the efforts of many—from legislators, policymakers and the court system to health providers, non-government specialist support services and individuals.

All of this was evident at the South West Sydney Domestic Violence Committee’s annual Domestic and Family Violence Conference in Sydney last week. Keynote speakers were from government, academia, the health sector and people with lived experience of DFV. Despite their diverse experiences and knowledge of the sector, there were some clear take-home messages.

- Personal stories are powerful. From empowering victims to mobilising the community, the personal stories of people with lived experience of violence are critical for change. We were humbled to hear the stories of Amani Haydar, Synthia Huynh and Shadow Minister for Prevention of Family Violence, Trish Doyle, all of whom witnessed their fathers perpetrate violence against their mothers. Amani reflected that reclaiming her narrative has helped her move from being a victim to a survivor and advocate. Synthia and Trish also stressed the importance of giving voice and decision-making power to victims. And Dr Michael Flood, researcher on masculinities and violence, reported that personal stories have been a powerful way to engage men who may otherwise not have ‘cared’ about DFV.

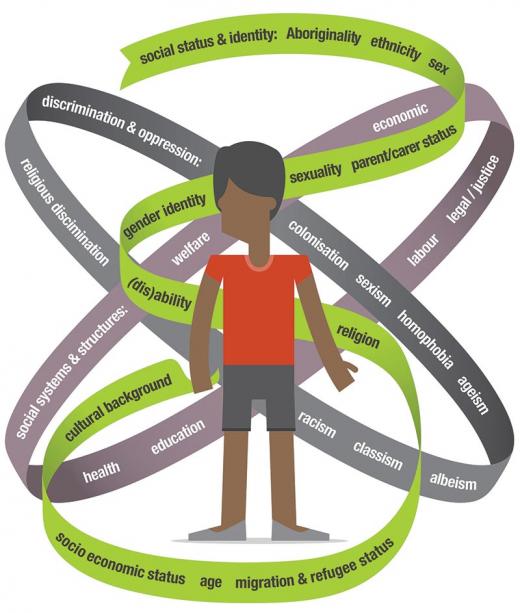

- Intersectionality is key. We were reminded that ‘intersectionality’ is more than a buzzword. It is key to delivering culturally-safe and trauma-informed services. Alissar El-Murr from the Australian Institute of Family Studies encouraged us not to pathologise, but to recognise individuals’ diverse cultures and experiences. Dr Flood also noted that an intersectional lens, recognising the range of individual and structural disadvantages at play, is needed to understand inequality and respond appropriately.

- We need to engage perpetrators. Increasingly, the sector is recognising the gendered nature of DFV, calling for a ‘gender transformative’ (or, dare we say it, ‘feminist’) approach to addressing the key drivers of violence. Men’s Behaviour Change programs aim to do this, working with men who use violence and abuse to provide counselling, case management, information and support. Melinda Norton and Carolyn Thompson from Women NSW reported that in NSW, there are now nine registered Men’s Behaviour Change programs operating in 36 locations under the recent Practice Standards. Melinda reflected on the importance of working with all men to prevent violence in the first instance, and with perpetrators to prevent re-offending. Dr Flood also stressed the need to engage men – not to replace the voice of women – but to establish accountability and challenge cultural norms related to masculinity.

- Change is multi-level and holistic. The factors that drive violence against women happen at the individual, interpersonal, organisational and community levels. So, responses will be more effective if they take an integrated and holistic approach, mutually reinforcing one another across the social ecology. This requires coordination and collaboration across sectors and the government and non-government sectors to ensure a uniform understanding of and approach to DFV. Most acknowledged that there are currently not enough services and programs to meet demand, and that further funding and political support is needed to embed structural and cultural change.

- Evidence supports change. Finally, the conference underscored the importance of using evidence to inform positive change. Melinda and Carolyn from Women NSW spoke of the value of evaluation in designing evidence-based programs with clear theories of change. This is particularly important, given that there have been few public, high-quality impact evaluations of DFV policies and programs in Australia to date (though this is slowly evolving) and more research is required to understand ‘what works’.[2] Dr Maria Nittis, Forensic Medical specialist shared her fight to embed the use of forensic imaging in hospitals when responding to DFV incidents. Despite institutional resistance, she stressed the value of using this evidence to support positive legal outcomes for victims in court. Dr Sue Heward-Belle reminded us of the power of practice-based knowledge, drawing on the valuable experience of DFV practitioners to develop an evidence-based manual that will support future practice.

It was reassuring that the learnings shared at the conference echoed our own approach to working in the sector. When evaluating DFV programs and system reform initiatives, we are committed to giving voice to people with lived experience, recognising intersectional disadvantage, and critically assessing all available evidence to make informed recommendations. It is our experience that combined, stats and stories can have a powerful impact on decision-makers.

[1] Available at: https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/08_2014/national_plan_accessible.pdf

[2] Webster, K. and Flood, M. (2015), Framework foundations 1: A review of the evidence on correlates of violence against women and what works to prevent it. Companion document to Our Watch, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) and VicHealth, Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia, Our Watch, Melbourne, Australia.

Image credit: Our Watch